It’s hard to believe that we are almost at Thanksgiving already. For such an irritating year (in terms of the collapse of volatility, May excepted), 2006 has passed relatively quickly. Only a few weeks to go until YTD P/L’s flip back to zero (indeed, for many hedge funds and investment banks, only a few days!), which hopefully will bring increased risk appetite and volatility back to financial markets.

The portfolio has fared pretty well over the weekend, with a sharp decline in Aussie stocks offsetting the rallies in Treasuries and EUR/JPY. Macro Man is disgusted with himself for losing money in the latter, as the short EUR/JPY trade has been one of the costliest in foreign exchange over the past three years. He will bid 1.2785 to cover the short EUR leg, then perhaps look to sell out the yen on a decline in USD/JPY. Currencies remain a wretched market, and perhaps Macro Man would be advised to abandon them altogether for the time being.

In trawling the web over the weekend, Macro Man was startled to see one well-known hedge fund manager call the current US equity market environment “one of the best shorting opportunities in years.” Is this really the case? A bearish argument, it seems, would hinge on three key planks: valuation, positioning, and future earnings. Macro Man attempted to examine each of these arguments from an honest and hopefully unbiased perspective to determine whether we really are perched at the edge of a precipice.

Valuation does not appear to be a significant obstacle to future equity gains. The current S&P500 trailing P/E ratio of 17.6 is relatively low by the standards of the last 20 years, coming in at just the 25th percentile. Meanwhile, both Treasury and corporate yields are near their lows of the same period, suggesting a relatively attractive valuation for equities on the basis of the so-called “Fed model.” Skeptics about the quality of SPX trailing earnings must reconcile their views with the persistent strength of NIPA earnings, which are tax-based and cover the entirety of corporate America. To put things in perspective, the chart below illustrates S&P 500 earnings per share and price over the past several years: observe how much higher EPS is than the last time the index was at 1400! Macro Man is forced to conclude that while US equity valuations may not be especially attractive relative to the rest of the world, the US market actually looks cheap relative to its own history.

The portfolio has fared pretty well over the weekend, with a sharp decline in Aussie stocks offsetting the rallies in Treasuries and EUR/JPY. Macro Man is disgusted with himself for losing money in the latter, as the short EUR/JPY trade has been one of the costliest in foreign exchange over the past three years. He will bid 1.2785 to cover the short EUR leg, then perhaps look to sell out the yen on a decline in USD/JPY. Currencies remain a wretched market, and perhaps Macro Man would be advised to abandon them altogether for the time being.

In trawling the web over the weekend, Macro Man was startled to see one well-known hedge fund manager call the current US equity market environment “one of the best shorting opportunities in years.” Is this really the case? A bearish argument, it seems, would hinge on three key planks: valuation, positioning, and future earnings. Macro Man attempted to examine each of these arguments from an honest and hopefully unbiased perspective to determine whether we really are perched at the edge of a precipice.

Valuation does not appear to be a significant obstacle to future equity gains. The current S&P500 trailing P/E ratio of 17.6 is relatively low by the standards of the last 20 years, coming in at just the 25th percentile. Meanwhile, both Treasury and corporate yields are near their lows of the same period, suggesting a relatively attractive valuation for equities on the basis of the so-called “Fed model.” Skeptics about the quality of SPX trailing earnings must reconcile their views with the persistent strength of NIPA earnings, which are tax-based and cover the entirety of corporate America. To put things in perspective, the chart below illustrates S&P 500 earnings per share and price over the past several years: observe how much higher EPS is than the last time the index was at 1400! Macro Man is forced to conclude that while US equity valuations may not be especially attractive relative to the rest of the world, the US market actually looks cheap relative to its own history.

Ah, but it has rallied since June in virtually a straight line. Surely the market is long and soon to be wrong? Macro Man would concur that the speculative market is now long US equities, but positions look relatively light. As far as he can make out, the over-arching story of the past five months has been short-covering. Anecdotal and survey evidence suggest that active global index fund managers have underweighted the US for several years, with corresponding overweights in Europe, Japan, and EM. Moreover, the chart below illustrates the net long S&P 500 speculative futures positions as a percentage of the outstanding spec positions. It is interesting to note that the market has been persistently short for most of the past four years, with most of the long positions during that time coming during the annual Q4 rally. Perhaps the current modest long will meet the fate of prior longs since 2002, and quickly unwind. Nevertheless, any long that exists is, as far as Macro Man can see, very modest by the standards of history. As such, he cannot see that positioning can credibly be used as a rationale for the US market being an outstanding short, especially when other markets exhibit (anecdotally, at least) greater length and a higher beta.

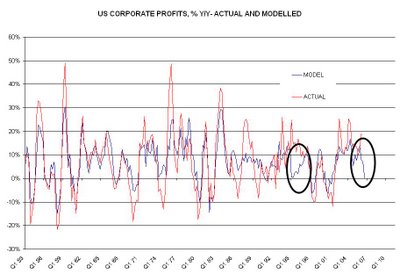

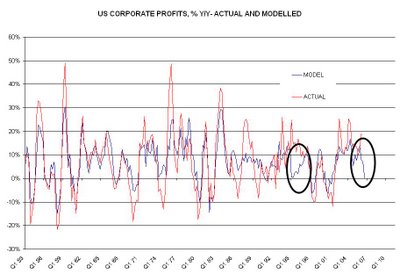

What about future earnings? It is here that the bear argument makes its strongest case. Although Macro Man does not believe that the housing market necessarily leads to recession, he is concerned by other, more persistent drivers of corporate profits- namely wage growth and the inventory cycle. A simple macroeconomic model which has proven to be remarkably successful in modeling annual profit growth is flashing a bright red warning light. The model, which displays a correlation of 0.82 with actual NIPA y/y profit growth since 1953, suggests that economy-wide profit growth should slow to 0% y/y in the relatively near future. The model is not yet pricing recession, but rather a period of stagnation. Macro Man is not positive what the price implications for equities would be is profit growth flatlines for a few quarters, but something plus or minus 10% or so seems reasonable. Such an outcome would imply that equities are a relatively unattractive long, but by no means the sale of the century.

One caveat to note is one of the few prior notable misses of the macro profits model. In 1995, after a period of prolonged Fed tightening, the model suggested a deceleration to zero profit growth. In fact, profit growth showed surprising resilience, and the US stock market put in a straight-line rally of fairly memorable proportions. This is the bull case: that 2006 = 1995. As yet, Macro Man is unconvinced by this argument, as we need to see how resilient profits prove to be during this period of low nominal GDP growth. In the end, he is left more or less where he started. He is suspicious of the resilience in profits to date, but cognizant that neither positioning nor current valuation are gale-force headwinds. Indeed, he suspects that the “melt-up” scenario would be relatively painful for quite a few smart investors, which is why he slapped on the risk reversal hedge on Friday.