It's a little-known fact, but Macro Man is the richest man in the world. Why, he can hear you ask, is his name not known across the globe, and his face not splashed on business magazine covers from Wall Street to Shanghai?

Well, in truth, most of his wealth is unrealized. But last week, he borrowed a pound (£1) from a friend when short of change. Rather than pay his friend back, in compensation he offered his mate a small share (1/500 billionth, to be precise) of his new company, Macro Man Industries, in exchange for his pound coin. Macro Man retains ownership of the remaining 499,999,999,999 shares. When his mate accepted the MMI equity stake, Macro Man's share was immediately valued at £499,999,999,999, which is more than a trillion dollars at today's exchange rates. It's good to rich, baby!

Such logic, with only a slight exaggeration, is what underpins the trillion dollar valuation of PetroChina. To be sure, PetroChina is a real company with real assets, and in that sense it does differ from Macro Man Industries, whose only asset is the meagre talents of your humble scribe. But the Chinese government controls almost 99% of the shares, leaving insitutions and retail punters to fight over the remaining one-and-a-bit percent listed in Shanghai, Hong Kong, and via ADRs. The result is a supply/demand imbalance that is eerily reminiscent of the Nasdaq craze in late 1999/early 2000, when the only meaningful data point for corporate highfliers like WebVan and Pets.com was the offer side of the bid/ask spread.

Further evidence of the bubblicious market environment in China and Hong Kong comes from Alibaba.com, a recent HK IPO that is now valued at a cool US$25 billion. The company's primary asset appears to be that it has a website, according to one Singapore-based fund manager. (UPDATE: Bloomberg has removed the quote from the story. Drat!) Hmm...so does Macro Man Industries. Perhaps that £500 billion valuation wasn't that far off! Regardless, Macro Man would advise investors in Alibaba to beware of the Forty Thieves: if you can't find them, they just might be the guys who sold you your stock.

These anecdotes make Macro Man all the more confident that a bum-clenching correction/reversal in all things China is inevitable. Not to say that it will happen imminently, of course; these things have a habit of taking longer than you might think. That having been said, the consensus seems to be that the time to sell China will be after next summer's Olympic Games. Presumably that means that 'smart money' will be selling in the spring....so could the great crash happen in Q1 or Q2? Stranger things have happened. (As an aside, there was a typo in yesterday's post. Macro Man bought 50, rather than 500, of the Hang Seng puts. He's happy to risk $350k on the trade, but not $3.5 million!)

Elsewhere, price action in Western equities continues to confound. The steady stream of bad news from the credit space remains a pressure point for stocks....and yet they keep holding in there. For the past couple of weeks, someone/something big appears to lurk at 1490 on the cash S&P 500 index. If we ever get any good news on credit, the market could be posied for quite a nice rally.

A market that has had little difficulty in falling this year is of course Japan, which a quick look at WEI on Bloomberg reveals is the worst performing major market in both local currency and dollar terms. A bit of a data milestone was reached last night, as the leading economic index printed 0 for just the fourth time since 1970 (the others were in 1974 and two months in 1997, in case you were wondering.) Macro Man's preferred measure, the 3 month average reading of the LI, unsurprisingly also lurched lower. Somehow, with an ultra-competitive yen and a booming China, Japan once again finds itself perched on the brink of recession. Go figure....

A market that has had little difficulty in falling this year is of course Japan, which a quick look at WEI on Bloomberg reveals is the worst performing major market in both local currency and dollar terms. A bit of a data milestone was reached last night, as the leading economic index printed 0 for just the fourth time since 1970 (the others were in 1974 and two months in 1997, in case you were wondering.) Macro Man's preferred measure, the 3 month average reading of the LI, unsurprisingly also lurched lower. Somehow, with an ultra-competitive yen and a booming China, Japan once again finds itself perched on the brink of recession. Go figure....

Of course, the US has its own problems, and last night's release of the Fed senior loan officer survey unsurprisingly revealed a sharp tightening of lending standards for residential mortgages and, somewhat more surprisingly, commercial real estate. Standards for commerical and industrial loans also tightened, but less than during the LTCM episode and the last recession, as the Fed chart below illustrates. For the recessionaires to be proven correct, you'll need to see a further tightening of these types of loans; that having been said, the survey provides yet another piece of data that the credit cycle has turned and that spreads should widen on a structural basis.

Of course, the US has its own problems, and last night's release of the Fed senior loan officer survey unsurprisingly revealed a sharp tightening of lending standards for residential mortgages and, somewhat more surprisingly, commercial real estate. Standards for commerical and industrial loans also tightened, but less than during the LTCM episode and the last recession, as the Fed chart below illustrates. For the recessionaires to be proven correct, you'll need to see a further tightening of these types of loans; that having been said, the survey provides yet another piece of data that the credit cycle has turned and that spreads should widen on a structural basis.

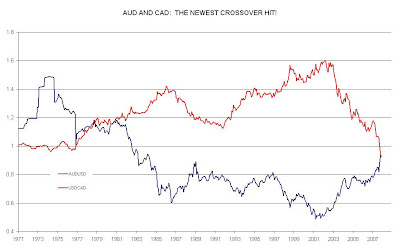

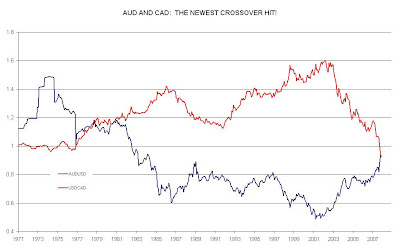

In FX land, a very significant milestone beckons. No, not the all time low in USD/Europe (though that does in fact beckon as well), but the crossover of the USD/CAD and AUD/USD exchange rates. Anyone who was trading currencies six or seven years ago, when USD/CAD traded 1.60 and AUD/USD at 0.48, must be shaking their heads at this development. Macro Man wonders how many misquotations will occur today, given that USD/CAD and AUD/USD tend to be on top of each other on most FX punters' quote screens.

In FX land, a very significant milestone beckons. No, not the all time low in USD/Europe (though that does in fact beckon as well), but the crossover of the USD/CAD and AUD/USD exchange rates. Anyone who was trading currencies six or seven years ago, when USD/CAD traded 1.60 and AUD/USD at 0.48, must be shaking their heads at this development. Macro Man wonders how many misquotations will occur today, given that USD/CAD and AUD/USD tend to be on top of each other on most FX punters' quote screens.

Finally, Macro Man was a fool, a fool! to question the currency trading acumen of Gisele Bundchen yesterday. EUR/USD has traded within a few pips of the equivalent all-time low in USD/DEM, and it would appear to be only a matter of time before that threshold is breached. Henceforth, to aid him in his trading, Macro Man has decided to wear one of those trendy rubber bracelets emblazoned with the slogan WHAT WOULD GISELE DO?

Finally, Macro Man was a fool, a fool! to question the currency trading acumen of Gisele Bundchen yesterday. EUR/USD has traded within a few pips of the equivalent all-time low in USD/DEM, and it would appear to be only a matter of time before that threshold is breached. Henceforth, to aid him in his trading, Macro Man has decided to wear one of those trendy rubber bracelets emblazoned with the slogan WHAT WOULD GISELE DO?

Well, in truth, most of his wealth is unrealized. But last week, he borrowed a pound (£1) from a friend when short of change. Rather than pay his friend back, in compensation he offered his mate a small share (1/500 billionth, to be precise) of his new company, Macro Man Industries, in exchange for his pound coin. Macro Man retains ownership of the remaining 499,999,999,999 shares. When his mate accepted the MMI equity stake, Macro Man's share was immediately valued at £499,999,999,999, which is more than a trillion dollars at today's exchange rates. It's good to rich, baby!

Such logic, with only a slight exaggeration, is what underpins the trillion dollar valuation of PetroChina. To be sure, PetroChina is a real company with real assets, and in that sense it does differ from Macro Man Industries, whose only asset is the meagre talents of your humble scribe. But the Chinese government controls almost 99% of the shares, leaving insitutions and retail punters to fight over the remaining one-and-a-bit percent listed in Shanghai, Hong Kong, and via ADRs. The result is a supply/demand imbalance that is eerily reminiscent of the Nasdaq craze in late 1999/early 2000, when the only meaningful data point for corporate highfliers like WebVan and Pets.com was the offer side of the bid/ask spread.

Further evidence of the bubblicious market environment in China and Hong Kong comes from Alibaba.com, a recent HK IPO that is now valued at a cool US$25 billion. The company's primary asset appears to be that it has a website, according to one Singapore-based fund manager. (UPDATE: Bloomberg has removed the quote from the story. Drat!) Hmm...so does Macro Man Industries. Perhaps that £500 billion valuation wasn't that far off! Regardless, Macro Man would advise investors in Alibaba to beware of the Forty Thieves: if you can't find them, they just might be the guys who sold you your stock.

These anecdotes make Macro Man all the more confident that a bum-clenching correction/reversal in all things China is inevitable. Not to say that it will happen imminently, of course; these things have a habit of taking longer than you might think. That having been said, the consensus seems to be that the time to sell China will be after next summer's Olympic Games. Presumably that means that 'smart money' will be selling in the spring....so could the great crash happen in Q1 or Q2? Stranger things have happened. (As an aside, there was a typo in yesterday's post. Macro Man bought 50, rather than 500, of the Hang Seng puts. He's happy to risk $350k on the trade, but not $3.5 million!)

Elsewhere, price action in Western equities continues to confound. The steady stream of bad news from the credit space remains a pressure point for stocks....and yet they keep holding in there. For the past couple of weeks, someone/something big appears to lurk at 1490 on the cash S&P 500 index. If we ever get any good news on credit, the market could be posied for quite a nice rally.

A market that has had little difficulty in falling this year is of course Japan, which a quick look at WEI on Bloomberg reveals is the worst performing major market in both local currency and dollar terms. A bit of a data milestone was reached last night, as the leading economic index printed 0 for just the fourth time since 1970 (the others were in 1974 and two months in 1997, in case you were wondering.) Macro Man's preferred measure, the 3 month average reading of the LI, unsurprisingly also lurched lower. Somehow, with an ultra-competitive yen and a booming China, Japan once again finds itself perched on the brink of recession. Go figure....

A market that has had little difficulty in falling this year is of course Japan, which a quick look at WEI on Bloomberg reveals is the worst performing major market in both local currency and dollar terms. A bit of a data milestone was reached last night, as the leading economic index printed 0 for just the fourth time since 1970 (the others were in 1974 and two months in 1997, in case you were wondering.) Macro Man's preferred measure, the 3 month average reading of the LI, unsurprisingly also lurched lower. Somehow, with an ultra-competitive yen and a booming China, Japan once again finds itself perched on the brink of recession. Go figure.... Of course, the US has its own problems, and last night's release of the Fed senior loan officer survey unsurprisingly revealed a sharp tightening of lending standards for residential mortgages and, somewhat more surprisingly, commercial real estate. Standards for commerical and industrial loans also tightened, but less than during the LTCM episode and the last recession, as the Fed chart below illustrates. For the recessionaires to be proven correct, you'll need to see a further tightening of these types of loans; that having been said, the survey provides yet another piece of data that the credit cycle has turned and that spreads should widen on a structural basis.

Of course, the US has its own problems, and last night's release of the Fed senior loan officer survey unsurprisingly revealed a sharp tightening of lending standards for residential mortgages and, somewhat more surprisingly, commercial real estate. Standards for commerical and industrial loans also tightened, but less than during the LTCM episode and the last recession, as the Fed chart below illustrates. For the recessionaires to be proven correct, you'll need to see a further tightening of these types of loans; that having been said, the survey provides yet another piece of data that the credit cycle has turned and that spreads should widen on a structural basis. In FX land, a very significant milestone beckons. No, not the all time low in USD/Europe (though that does in fact beckon as well), but the crossover of the USD/CAD and AUD/USD exchange rates. Anyone who was trading currencies six or seven years ago, when USD/CAD traded 1.60 and AUD/USD at 0.48, must be shaking their heads at this development. Macro Man wonders how many misquotations will occur today, given that USD/CAD and AUD/USD tend to be on top of each other on most FX punters' quote screens.

In FX land, a very significant milestone beckons. No, not the all time low in USD/Europe (though that does in fact beckon as well), but the crossover of the USD/CAD and AUD/USD exchange rates. Anyone who was trading currencies six or seven years ago, when USD/CAD traded 1.60 and AUD/USD at 0.48, must be shaking their heads at this development. Macro Man wonders how many misquotations will occur today, given that USD/CAD and AUD/USD tend to be on top of each other on most FX punters' quote screens. Finally, Macro Man was a fool, a fool! to question the currency trading acumen of Gisele Bundchen yesterday. EUR/USD has traded within a few pips of the equivalent all-time low in USD/DEM, and it would appear to be only a matter of time before that threshold is breached. Henceforth, to aid him in his trading, Macro Man has decided to wear one of those trendy rubber bracelets emblazoned with the slogan WHAT WOULD GISELE DO?

Finally, Macro Man was a fool, a fool! to question the currency trading acumen of Gisele Bundchen yesterday. EUR/USD has traded within a few pips of the equivalent all-time low in USD/DEM, and it would appear to be only a matter of time before that threshold is breached. Henceforth, to aid him in his trading, Macro Man has decided to wear one of those trendy rubber bracelets emblazoned with the slogan WHAT WOULD GISELE DO?

27 comments

Click here for commentsChina is in a bubble, but I think we are probably closer from the start of a bubble rather than the peak as AG suggested. AG famously used the phrase “irrational exuberance” in Dec, 1996 – 3 years and 4 months before Nasdaq peaked...

ReplySo yes, China is in a bubble, but the bubble's not gonna burst before AG turns bullish...

Let me start my arguments by quoting both Andy Xie:

"China's urban residential properties and listed shares in the local and foreign stock market are worth 3.5 times GDP. Both Japan and Hong Kong peaked near 10 before bursting… "

" the value of China's residential properties is 1.7 times GDP. Japan's was 4.5 in 1989 and Hong Kong's 7.5 in 1997."

"Over two-thirds of these are owned by government entities. The shares that are liquid and locally listed are merely Rmb9,000bn, or 38 % of GDP… In addition, the controlling shareholders of privately owned and listed companies cannot sell down their shares even when they think the shares overvalued. ..”

. High inflation

. Low bank deposit rate

. Strict capital control (money can’t get out of the country)

. Currency is not exchangeable

. Stocks r sky-rocketing

Am I talking about China? Nope, it’s Zimbabwe:

Zimbabwe Industrials up >12,000% yoy, deducting inflation (which runs at 1,729% yoy), stocks there are still sky-rocketing.

Zimbabwe example is a bit extreme. But it demonstrates how changes in stock prices can be driven by monetary conditions, and not changes in GDP. Because there are no alternatives: keeping Zimbabwean dollars in ur pocket, and they’ve already lost a chunk of their value by the next day. Putting money in the bank is not much better. Investing in government bonds is financial suicide, converting wealth to other currencies is limited by strict rules.

I use Zimbabwe's case to argue that Chinese stocks have much further to go UP. What happening there is similar to what happening in China right now (although on a different scale). The only main difference is Chinese stocks are also supported by economical fundamentals apart from monetary conditions -- Chinese GDP is growing at 11% annually. Chinese stocks have more reasons to go up… Here is a list I constructed below:

. High growth

. High inflation (6.2% latest print) while deposit rate is at 3.87%

. Tight capital control

. Limited investment products/opportunities at home

Short sell is banned and no futures

. Mounting foreign reserve

. A share largely illiquid (due to reasons explained by Andy Xie)

. Burst of US housing bubble lead capital flowing to Asia

. Hot money speculating RMB appreciation

. Comparing with other BRICs (and Eastern European stocks), Chinese stocks still under-perform over the last 4 yrs

. Hearing rumours back home that after 17th Congress, most of the new leaders promoted r all stronger believer of rapid growth which means PBoC will be less independent to make economy tightening policys

sry, after posting i realized that comment is a bit too long n sqeezed the space here!

ReplyJapan would look like a basket case without the U.S. and China. Their longest expansion since World War II has pushed Japanese interest rates all the way up to 0.5 percent. Not to impute nefarious motives to them, but they have certainly done their part (via monetary policy) toward contributing to all of the bubbles all over the world.

ReplyWhile I certainly have some sumpathy for the notion that Chinese property is unlikely to collapse for the reason you mention, Chinese equity is much more vulnerable- market cap as a % of GDP is swiftly approaching levels that were associated with reversal in Japan and Taiwan, and there are a LOT of newcoemrs to the market.

ReplyThe problem with the Zim analogy is that the Zim dollar has devalued from 250 to 30,000, which means that the hard currency appreciaiton of the Zim market is basically zero.

That logic is also the underpinning of "mark to market" for subprime CDOs, and makes as much sense there. If a market participant was holding a CDO for a yield, what sense does it make to "value" it based on the price given another market participant, esp. when the selling participant was forced to sell based on margin calls ..

ReplyI think the logic of CDO pricing is somewhat different, and revolves around the maxim of "don't ask a question that you don't want to know the answer to."

ReplyOne of the reasons for the seize-up in turds is that no one actually wants to know where the stuff is, so banks are reticent to trade lest the voyage of price discovery take them over the edge of a cliff.

Sadly we are approaching the point where the dollar is going to keep slowing sliding and stocks actually begin to sell off. Right now the dollar doesnt seem so bad because somehow equities are holding in, but I would bet my first born that they dont hold the majority of there gains for the year for the next 8 weeks. Then we'll be looking at sp 1350 and oil somewhere in the 80's. Ouch.

ReplyLet's assume that several thousand of the 500 billion shares of Macro Man Industries (MMI) are in circulation, are relatively illiquid, and are held by institutions who have marked their value based on a recent trade of £499,999 per share.

ReplyNow assume some scandal occured at MMI, and a few dozen shares exchanged hands at much lower prices, say ... £100,000 per. Everybody who owns it has to mark down?

Now assume that, after the scandal but before any shares traded hands, the holders of MMI made a "gentlemen's agreement" or perhaps a "prisoner's dilemma" occurred, and nobody traded them at the expected low price, because nobody had any incentive to.

My point: MMI, PetroChina, and CDOs are priced identically. In the lack of a liquid market, a more complex model is used, but what is the closing price at the end of a reporting period, other than a simple model of valuation?

I see what you are saying. My take is that if something actually trades, the banks pretty much have to value it there whether they want to or not.

ReplySo perhaps the better analog is that some horrible event (call it 'reality') causes shares of MMI to fall from £499,999/share to £100,000/share.

Everyone long MMI has to mark their sheets there. No shares of NoDooDahs.com traded, however. Even though NoDooDahs.com has the same inherent charactristic as MMI (in our case, a bloke with a keyboard; in CDOs, they're chock full o' turds), dealers keep their NoDooDahs.com inventory marked at cost (or whatever their 'model' says), despite the trading price of MMI clearly suggesting that NDD.com should be marked lower.

As an aside, if you know anyone who may be interested in paying £499,999 for a share of MMI, let me know ;)

The complication with bonds is their uniqueness. T-bills and T-bonds have different maturities, so the compilation is modeled to produce an index price. If you throw in not only different maturities, but different terms and slightly different risk profiles, you might have a model for A-Rated corporates. Now consider CDOs compiled of different mortgages with different deadbeats holding them!

ReplyThe market price on a stock boils down to an opinion, at least in most cases it is a compilation of opinions from varied participants in a liquid market of identical commodities (shares of MMI). The market price on a CDO?

In the current mania (manias can be negative), I don't blame them for not trading them. Assuming an entity could survive the markdowns on their CDO holdings, in a year, they will be marking them UP.

The hullabaloo about mark to market and mark to model is much sound and fury, signifying nothing.

Yes, I was merely trying to use the analogy of illiquid unlisted 'shares' (ie, MMI, NDD.com) to remain conssitent with prior examples...replace our debt for our shares, and the analogy becomes closer to reality.

ReplyIt does seem likely that that some insitutions still have inventory marked too high...I've heard stories of hedge funds not making as much from their subrpime shorts as they should because of dodgy marking from prime brokers.

That having been said, the market seems intent trying to price all of this stuff at zero, or so it seems; as you suggest, there is very likely upside toe vntual valuaitons from what is currently being priced in some brokers' share prices.

nodoodahs:

Replywhat sense does it make to "value" it based on the price given another market participant, esp. when the selling participant was forced to sell based on margin calls ..

How can one distinguish between selling relating to a margin call dictating the marginal price, and say for example, selling of Enron stock "at any price" by for example friends Jeff Skilling with knowledge the end is nigh? IF something is so cheap, where are all the buyers?? They are scared witless that its worth NOTHING (or slightly more than nothing, and by the time one's lawyers shag their lawyers, and administration and court fees and time-value-t-settlement it might as well be NOTHING, even if its a little something more than nothing.

"In the lack of a liquid market, a more complex model is used, but what is the closing price at the end of a reporting period, other than a simple model of valuation?"

I was discussing "valuation" with the Sr. Partner of the hedge fund practice at one of the largest accounting firms recently about why, their opinion of my plain-vanilla fund is so rife with qualifications as to make it almost worthless. YET, if a hedge fund owns 15% of even a company, a position that would take months to trade out of, with enormous impact or immediately at a deep discount, doesn't qualify this and marks it to last. They won;t touch market-impact, liquidity, or sensitivity of both to valuation. Nope. Just pretend and assume "what is" will continue to be". But

valuation is stochastic and unknowable, but you gotta try. More important: anyone under the impression that mark-to-market is reflective of anything except the most optimistic realizable valuation is either lying or stupid. It's amazing how buyers miraculously disappear when a seller arrives, and vice-versa. Look at the quant-markdowns when normal liquidity-providers tried to sell into a market where all the liquidity-providers were recursively rtying to liquidate in the market (or at best, were "on strike")!

The hullabaloo about mark to market and mark to model is much sound and fury, signifying nothing.

In a fractional reserve banking system, where liqudity can be conjured more or less out of thin-air, and the ability to fund and lend is based upob trust, the integrity of valuation is of crucial importance - even to the pension fund holding a risky-CDO tranche to maturity for yield. Needless to say, given the cascade effects of actuarial assumptions, it would be calamitous to wait until maturity for beneficiaries to discover that the paper is only "worth" 50 on the dollar, for the return consequences are immense. THIS is why leverage is poisonious! This is why bankers should be forced to be prudent, rather than driven to "do what everyone else is doing" in order to hit their numbers, including some of the most assinine financial engineering ever conceived by man, let alone by would-professionals....

If you channel your "inner Graham" you can see that the market price and the intrinsic value are not the same thing; "marking to market" is just "marking to model" and choosing the closing price as your model. A forced sale because some hedgie got their panties in a wad on leverage doesn't mean the asset is intrinsically worth less, it just means that a sale was recorded at a lower price.

ReplyThe lack of buyers is artificial on several levels.

The hedgies know whose asses are in cracks, and they're gunning them down, forcing sales at low prices to drive competitors out of business.

Cassandras are well-known for bloviating about manias on the long side, but seldom stop to think that market psychology can drive prices down below reasonable measures, too.

Nobody (almost nobody) wants to report buying them for fear of the public reaction *right now.* Give it time, the buyers will come out once CNBC stops the "sub slime" hype machine.

Jeezus f Christ, could you be any more blow-job-giving self-aggrandizing than the sentence "I was discussing 'valuation' with the Sr. Partner of the hedge fund practice at one of the largest accounting firms recently .."

Yep, there are different models of valuation for marking that are used based on equity class, and for some different securities in the same equity class, the models don't make sense. Your point is?

What I take from it is the point I already made, that liquidity makes for easier modeling, and lack of liquidity makes for harder modeling. I applied that to bonds but I agree that it could be extrapolated to large positions in companies, relative to the average liquidity. This problem is what almost wiped Jim Cramer's fund out, he had tons of regional bank stock that was illiquid during the crisis.

"anyone under the impression that mark-to-market is reflective of anything except the most optimistic realizable valuation is either lying or stupid." Does that apply to Joe Six-Pack having some GE in their self-directed IRA? Maybe you're a little dense, but "mark to market" is a MODEL of pricing. Or did you mean to type "model" instead of "market?" In response to that, the holders will tend to have an optimistic model, and the buyers will tend to have a pessimistic model, and a few responsible parties might try to have an accurate model (maybe they succeed, maybe they don't).

"It's amazing how buyers miraculously disappear when a seller arrives, and vice-versa."

Addressed above.

"In a fractional reserve banking system, where liqudity can be conjured"

Don't misuse the term liquidity, and don't mistake currency for liquidity, or increased liquidity for a monetary condition. The two are not the same.

"Needless to say, given the cascade effects of actuarial assumptions,"

I see no actuarial assumptions in my daily life that have "cascade effects." Could you elaborate? Perhaps you could ask one of the senior partners you talk to regularly?

If they wait until maturity, they are not selling the paper and don't care what the market price is. They have a claim on assets and would pursue it through the courts if necessary.

I agree that leverage is dangerous and should be used much more sparingly that it is.

do you feel a need to instrinsically be a d*ck, or just to model one?

ReplyOh, dear. Come now, we're all intelligent adults; let's try and keep it civil and avoid the pissing matches that have plagued and, IMHO, ruined a lot of the other sites out there. It's more than OK to disagree, but let's leave the insults on the playgorund.

Replynodoodahs,

ReplyYou haven't been rude to me, so maybe I'll try and answer you.

I think the basic problem is that you're trying to construct some sort of an objective theory of value. You believe that an asset can have value that is somehow not expressed in its market price. Marx's "labor theory" is one of the best known theories of objective value, for example.

All sensible economists for about the last hundred years have agreed that value is subjective - that whatever "value" is, its only measurable epiphenomenon is its market price.

Your theory of value does not strike me as Marxist in any way. It is certainly held by many people today who wouldn't piss on a Marxist if he was on fire. Your errors are much more subtle than Marx's. But they are errors nonetheless.

You are describing these securities as underpriced because you have some confidence in their actual return. You are confident that, to match the same identical expected value of the payment streams they represent, but using safe T-bills, you would have to expend many more current dollars. Therefore, you conclude that the current fire-sale prices are too low.

So why not be a buyer? Load up the cart. How many great fortunes have been made in distressed assets!

Keynes put it in a nutshell: because the market can stay illiquid longer than you can stay solvent.

In other words, by buying these distressed assets, you are running in the wrong direction during a bank run. Unwise by definition.

The reason the market cannot price these securities relative to T-bills is that (as Cassandra was trying to tell you) the financial market in its fractional-reserve, maturity-mismatched incarnation is an enormously powerful machine for transmuting demand for short-term money into long-term money.

When this machine shuts down, it enters a different equilibrium state (google Diamond-Dybvig). Direct demand, not generated by maturity transformation, for a zero-coupon bond at 10 years or 20 or 30 would certainly imply rates in the double digits. Maybe even triple digits.

Therefore, the market cannot price these distressed assets comparably to a safe asset such as a T-bill. Therefore, you cannot use this price relationship to compute the probability of default.

Therefore, though it may be your opinion that a certain security is good, the market cannot compute a consensus price that can be used to generate its guess for the default rate of instruments affected by Diamond-Dybvig contagion.

So why not use whatever the model spits out? Why not use the last price before the contagion started? Whatever. At this point, you are firmly in Macro Man Industries department.

See also Cassandra's theory of narrowing, which is highly pertinent to this discussion.

ReplyIn a narrowing situation, the winning asset class will be the one least affected by contagion. For example, do the same kinds of actors hold SubPrime CreditCardLoans(tm) and Honus Wagner baseball cards? Then it's time for Honus to go on EBay.

My impression is that a lot of people have been playing financial games in mortgage securities, a lot have been speculating in commodities. When the first bunch took the high dive off the short board, rational players who grokked the game theory started switching to the other - based on nothing but graph algorithms.

It would probably be presumptuous of me to suggest that in five years, Orange County will hold half its pension fund in big slabs of warm, juicy, butter-yellow mold. But I certainly wouldn't rule it out, and it's the logical endpoint of narrowing - at least in this impecunious spectator's opinion.

Stock values arrived at in extremis by Chinese investors with few other outlets, and minority share issuances that produce dizzy numbers, don't bode well for Shenzhen index. Why wait for the Olympics?

ReplyBy the way, valuation techniques are only useful in the absence of market prices, not as a substitute. Maybe the problem with dreck held by US institutions is a distorted market price (to wit, none.) IMO, banks and funds will dribble out the bad news on losses little by little, just enough to satisfy Sarbanes-Oxley disclosure requirements, on a quarterly basis. Next round: more of the same.

I'll ask the Sr. Partner at a Big Four Firm, whom I speak with often, to review my comments for "d*ckage." I believe I answered all of Cassy's questions.

ReplyNo, I'm not trying to construct any objective theory of value, so don't try to accuse me of doing so. Value is of course subjective in reality. What I'm trying to address is the ridiculousness of critiquing "mark to market" vs "mark to model" when all ANYONE ever does is mark to a model of one sort, or another. I'm also trying to address the issue of how accountants are forced to value based on "government" regulations and market mores, which, while possibly objective, is arbitrary, inconsistent, and flawed.

A closing price is just a price, it is actually at the center of a disagreement between value models.

If I think it's worth $5, I'm not gonna pay $5. I would be indifferent to $5. I might pay $4.99 tho. If the seller thinks it's worth $4.98, he's not gonna take $4.98. He might take $4.99 tho. A market price is at the center of a disagreement between value models.

The subjective value changes from time to time, and from participant to participant. The market price existed for one point in time between two parties, and there's nothing magical about the last market price for the next set of participants.

The Keynes quote was "irrational" not "illiquid." I have bought items on fire sales before, probably will again, although for now I'm sticking to a couple of strategic themes and not chasing opportunities in "whack a mole" fashion.

The "consensus market price" is a fallacy. There is a price at a point in time between two participants, and even pretending that a closing price today is "consensus" is nonsense, it just happened to the be the tick at 4 pm Eastern, and it will not be an unbiased estimate of the next transaction.

Marking to market IS marking to model, just a simple model, one that has as many flaws as any other.

In the long run, P/L is the only true test of our models' accuracy.

There is certainly nothing magical about any price. Whenever you use a past price, you are importing an arbitrary judgment into your model. Why one hour ago, not two hours ago? Why the price at close, and not at open?

ReplyBut for just about any security, it is extraordinarily difficult to predict the pattern of change between today's price and tomorrow's price. Unless you have some special pricing insight on that instrument - in which case you are not an accountant, but an entrepreneur - if you want to guess the price tomorrow, your best guess is the price today.

The result of this behavior, which of course is the consequence of arbitrage in an efficient market, is that financial snapshots even as much as three months old are useful for present calculations.

But this depends on the EMH, which assumes a market with a single price equilibrium. It's very different from using past prices as the best estimate of present prices in a market which is characterized by multiple price equilibria. Especially when you know that the market is in the course of a transition from one equilibrium to the other - ie, a bank run.

"There is certainly nothing magical about any price. Whenever you use a past price, you are importing an arbitrary judgment into your model. Why one hour ago, not two hours ago? Why the price at close, and not at open?"

ReplyWhat is the purpose of a price?

The price is an observable statistic which samples some otherwise difficult unobservables, namely the comparative vim and vigor of buyers and sellers to acquire and dispose. The psychological characteristics is what you want to measure, but you can't.

By this point of view, a more liquid instrument, as it trades more frequently, you hope, samples a greater space of individual vim and vigor amongst the buyers and sellers.

At least to first order, rather than zeroth order, VWAP is what a statistical mechanic might hence advocate over either open and close.

When you mark to model versus mark to market --- there is both a bias and variance degradation in your estimators.

I agree with the principle everything always is, in some way, "mark to model". However, money talks and bullshit walks, and having to trade negotiable cash separates people's bloviation from their actual will more efficiently than other techniques, like say waterboarding.

I'm not sure the psychology is what you want to measure. I think the price is what you want to measure.

ReplyOf course the former drives the latter. However, price is set not by the psychology of the whole market, but only by the marginal players. Eg, if my reserve price R is above the market price M, the difference (R - M) does not affect the market. See under "marginal revolution."

I agree that trading is better than waterboarding as a method of price discovery. This has always been a core contention of the Austrian School. Waterboarding and other forms of torture are best seen as price calculation algorithms. I'm sure many traders have felt an urge now and then to strap the market to a long piece of wood and apply the ol' soggy cloth, but von Mises proved incontrovertibly that the tactic cannot achieve its goals.

The key question is: why should I be interested in the market's psychology? The answer is that, since the market rewards successful predictors and punishes unsuccessful ones, it is likely to be dominated by good predictors. Thus "price taking" is rational behavior.

But the presence of a multiple equilibrium or other fundamental instability invalidates these arguments. Caveat emptor.

Price modeling 101...

ReplyYou've got $2000 saved up for the rent due tomorrow. Your buddy owes you 2 grand and he WILL pay you back today. You want to buy that Les Paul whose price has been modelled by the corner retailer, today only, at $2000. You grab the deal. Your buddy doesn't come through. Tomorrow morning you find yourself at the pawn broker who models the price of your new axe at $1000. You make the choice - move in to that nice cardboard box under the local overpass with your guitar, or with 1000 in your pocket as you await the day in which your pal's model syncs up with his own personal reality.

There is, at times and depending on perhaps extraneous circumstances, a distinct and non-academic difference between the modelling algorythms of buyers and sellers - and the fact that you need the money bad, if that be the case, becomes another input. If that is not the case, your spin that the thing is actually worth 2500 holds sway.

And yes, bad behaviour should be rewarded in an appropriate fashion. Perhaps go stand out in the hall for an hour.

ReplyKinnell MM , you lit the blue touchpaper there.

ReplyHope these guys aren't too busy discussing theory and miss the last flight out of DollarCity.

Feels like Helicopters and Embassy Roof time in FX land ..

@butler:

ReplyA well known phenomenon called a liquidity premium.

Most money in markets is made (transferred) by squeezes such as this.

I would contend that a highly liquid instrument is worth more than the same, illiquid, instrument for this reason - it is more useful when you are strapped for cash.

amazing how huge the influence of China is, at least on the margin..

Replyovernight they mumble something about currency diversification, which they later 'clarify' and it sends the dollar tumbling (im sure thats exactly what they wanted)

maybe the US at some stage - to stop the dollar from collapsing totally, will have to agree with the Chinese to hand mon.policy over to them. the yuan will be allowed to float freely, and the dollar will be pegged to it. the PBOC gets to decide what the dollar/yuan rate is.